Today, every Korean has a surname, but its roots began as a symbol of bloodlines limited to the royal and noble classes during the Three Kingdoms period. It has traversed over a thousand years to evolve from the verbal appellations of tribal communities, signifying power and status, into institutionalized names.

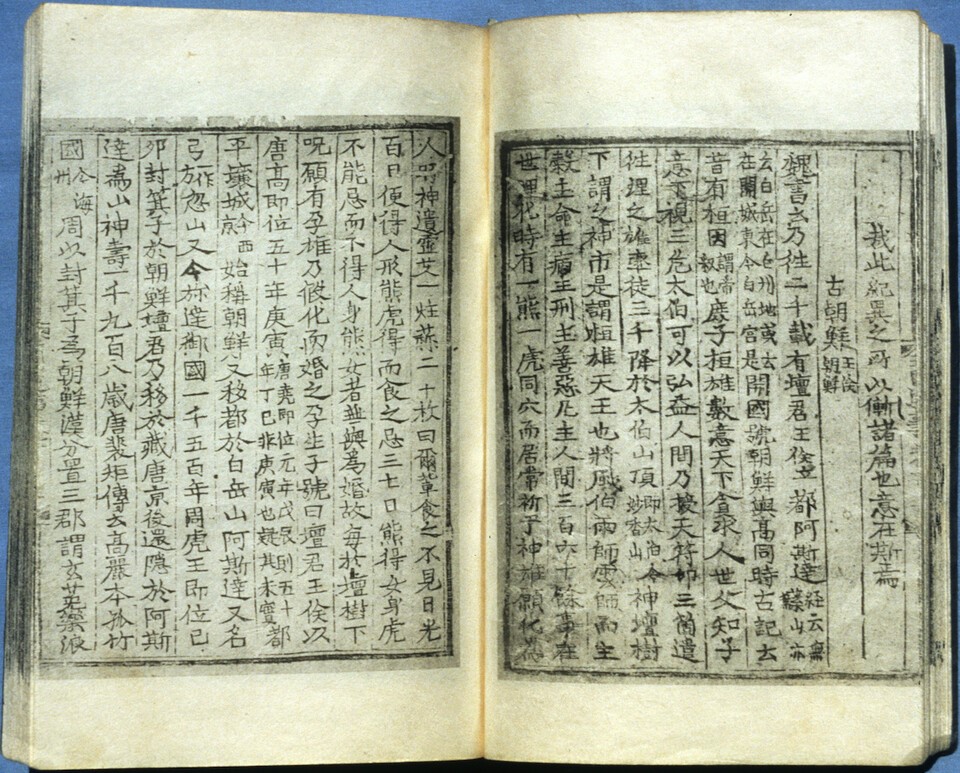

Traces of Names Starting from Ancient Joseon

The origins of Korean surnames trace back to ancient Joseon. According to some records, the national surname at that time was Han. Early use of surnames is known to have been a culture transmitted through Chinese immigrants. However, at that time, the distinction between surnames and given names was not clear, with unique names, animal names, and occupational names substituting for given names.

Names like Ma-ga, U-ga, Gu-ga of Buyeo originated from symbolic animals such as horse (ma), cow (u), and dog (gu). Rulers adopted the dignity of animals to reflect authority and rank.

Even titles like Cheon-gun and Sodo priest from Samhan were used like names during times when there were no surnames. Identification within the group relied on community memory and oral transmission. The current family name-first name system did not exist then.

Emergence of Surnames Exclusive to the Elite in the Three Kingdoms Era

During the Three Kingdoms period, surnames became exclusive to the royal and noble classes. In Silla, the Park, Seok, and Kim families successively ascended to the throne. Each had mythical origins – Park Hyeokgeose was born from an egg, and Kim Alji emerged from a golden chest, reinforcing the legitimacy of rule by imbuing bloodlines with sacredness.

Goguryeo’s royal family surname was Ko, including founder Chumo the Holy. Ulchi, Myeongnim, Song, and Ye were noble surnames, tasked with political and military responsibilities. Baekje adopted Buyeo as the royal surname, but real names were often recorded without a surname. After Baekje’s fall, Buyeo surnames almost vanished.

The six Silla tribes had surnames like Lee, Choi, Jeong, Bae, Son, and Seol, also belonging to the privileged classes. Commoners lived without surnames, and paternal lineage wasn’t publicly recorded.

A surname was akin to a seal symbolizing lineage – indicating social status more than parentage. Post the fall of Goguryeo and Baekje, their surnames disappeared from history, but Silla-based surnames continued into unified Silla and beyond.

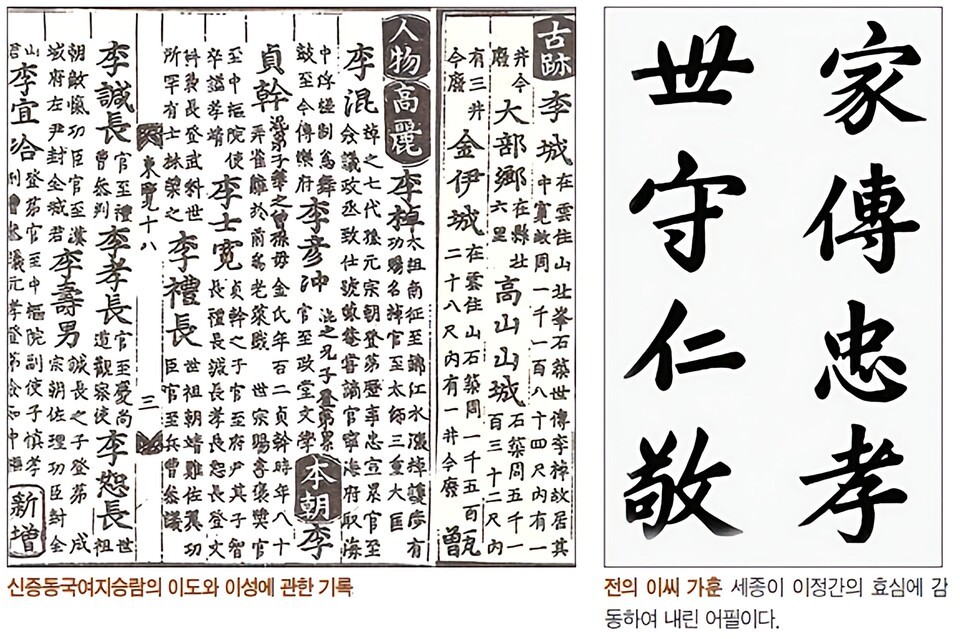

While Chinese character-based surname culture was introduced during this time, Korea didn’t just adopt it as is. Instead, it fused with the local social structure to develop the unique system of ‘Bon-gwan.’ Originating as a term indicating one’s hometown, over time, Bon-gwan became more critical than surnames as indicators of kinship identity.

The Beginning of Nationwide Spread with King Taejo of Goryeo’s Surname Policy

The nationwide dissemination of surnames began with King Taejo Wang Geon’s policy of bestowing surnames in 940, given to local gentries aiding in the Later Three Kingdoms unification. Surnames were rewards for loyalty, and Bon-gwan visualized regional identity.

Beyond mere birthplaces, Bon-gwan served as clan origin sites. Post-Goryeo, Bon-gwan evolved into a more prominent kinship identity, with Confucian order establishing bloodlines as the foundation of social order.

In 958, Goryeo King Gwangjong implemented the civil examination system, requiring surname possession for eligibility, prompting commoners to acquire surnames. By 1055, King Munjong banned exam participation without a surname, making surnames gateways to the bureaucracy and social mobility.

Surnames became the administrative, governance, and power base. By late Goryeo, the majority of commoners held surnames and Bon-gwan, with only slaves and some low-class individuals as exceptions.

Joseon Period: Status Mobility through Genealogy and Conferral Papers

In Joseon, surnames structured bloodline orders. Post-Imjin War, even lower classes acquired surnames. External slaves with financial means, affluent farmers, and merchants purchased noble status and surnames via conferral papers. Surnames were not just bloodlines but social assets.

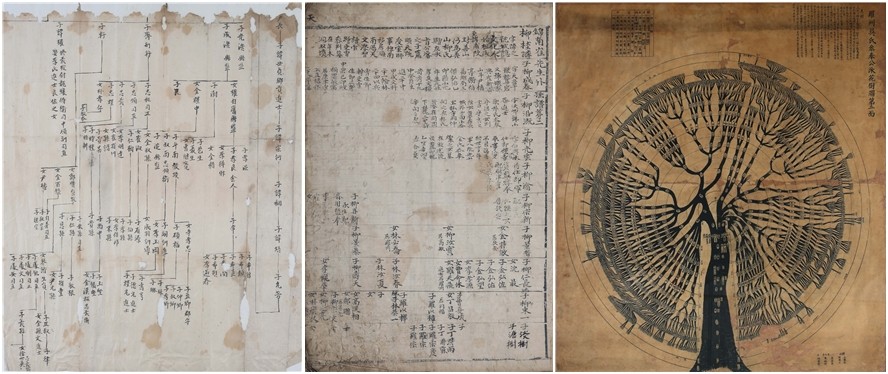

Genealogy culture advanced during this era. Initially documenting both male and female descendants, by mid-17th century, it shifted to a paternal-centric genealogy. Genealogies proved conditions for office, marriage, and regional hierarchy.

Villages formed by families sharing the same surname and Bon-gwan, establishing antecedent hamlets. Practices regarding ancestral rituals and marriages focused on bloodlines strengthened, and a prohibition on same-surname marriages was enacted.

Changing Status of Surnames with Modern Law

In 1909, the Korean Empire enforced the Civil Act, legally assigning surnames and Bon-gwan to all citizens, making surnames a legal right. The ensuing family head system entrenched a paternal-centric family structure, but with its abolition in 2008, the same-surname marriage ban vanished.

Modern Korea is a society of diverse surnames. As of 2015, the National Statistical Office confirmed 5,582 surnames, 4,075 of which cannot be represented with Chinese characters. Multicultural integration and naturalization are reshaping surname landscapes, with 4,179 Bon-gwan confirmed. Gimhae Kim, Miryang Park, and Jeonju Lee still dominate.

A Millennium-Long Journey, Surnames Are Korean History

Surnames no longer serve as markers of social position but as symbols of law, culture, and identity. Today’s society, where everyone has a surname, reflects the historical dismantling of what was a privilege exclusive to kings and nobles a thousand years ago. Surnames carry communal memories, persisting in evolution.

With the rise in multicultural families, new surnames are emerging. Naturalized citizens create their unique surnames, sometimes adding Bon-gwan to existing ones, forming independent lineages. This trend reflects the cultural diversity of Korean society while expanding the social significance of surnames.

Technologically, surname culture is modernizing with digital genealogies and online clan communities. The historical and identity roles of unique surnames are adapting flexibly with the times, reflecting both continuity and change.

Surnames are not merely parts of names; they are roots, records, and living cultural heritage left by eras and communities. It is not about ownership but about how they will be perpetuated.